Delaware River Approaching Drought Flow Threshold

Drought Emergency Could Impact Power Plants

“Trouble Ahead”?

Jon Hurdle at NJ Spotlight just wrote an important story about the implications for drought in the Delaware River basin – specifically regarding migration of the salt line towards water supply intakes for the cities of Camden and Philadelphia – read the whole thing.

I am glad Spotlight got it right, because NJ American really spun the Philadelphia Inquirer to create the misleading impression that South Jersey and the Delaware did not face drought conditions like North Jersey (read that story too).

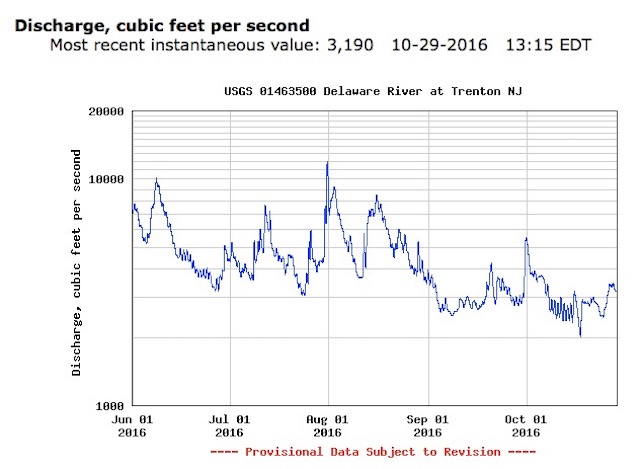

After reading them both, I checked the Delaware River flow at Trenton – see the above chart is from the USGS monitoring network.

The most recent flow data at Trenton is 3,190 CFS.

I also looked at the DRBC Drought Operating Plan to get a sense of the implications of a worsening drought, particularly the DRBC policy for curtailment of water allocations to users.

Power plants are by far the largest water users. A terrible irony that the fossil plants that are driving climate change – which exacerbates drought – are most at risk from drought. From DRBC:

Within the basin, uses related to power generation (thermoelectric) account for the majority of water withdrawals (68%). The next largest use is for public water supplies, or PWS (11%). However, in managing water resources, the withdrawal volume may not be as important as where and when the water is returned to the system. Water not immediately returned is considered consumptive use (see sec on 1.2).

More from DRBC

Power from WaterWhile water and electricity are usually not a good mix, making electricity traditionally requires a lot of water – 77% of all water use in the basin is involved in power generation. As our need for electricity has increased in the last twenty years, so has our use of water to generate it. How much is actually “consumed” (see above) depends on the type of cooling system used. Once-through systems use a heat absorber, use more water, but have a lower consumptive use (<1%). Systems that use tall evaporative cooling towers need less water, but have a high consumptive use (>90% is evaporated). The amount of water used to create electricity now accounts for one third of all the water used consumptively. Recently, rules were changed to require recirculating systems at new power generating plants. While requiring less water to run, such plants will have a higher percentage of consumptive use. This is a mixed result, since more water can remain in the rivers, but less will be immediately returned to be used again.

♦ Learn more about tracking supply and demand (pdf 4.1 MB; TREB Ch.2, pgs. 2-5)

According to Delaware River Basin Commission rules, when the flow at Trenton goes below 3,000 CFS for 5 consecutive days,

Lower Basin DroughtJust as there is minimum flow objective of 1,750 cubic feet per second (cfs) at Montague, N.J., the DRBC Water Code sets a minimum flow objective of 3,000 cfs at Trenton, N.J. (head of tide).

Why is there a Trenton flow target? The DRBC lower basin drought management plan focuses on controlling the upstream migration of salty water (referred to as the “salt front” or “salt line”) from the Atlantic Ocean through the Delaware Bay into the tidal river. The salt front’s location fluctuates along the tidal Delaware River as freshwater streamflows traveling downstream increase or decrease in response to hydrologic conditions, diluting or concentrating chlorides in the river. DRBC-directed releases from Blue Marsh Reservoir (located on the Tulpehocken Creek, a tributary of the Schuylkill River) and Beltzville Reservoir (located on the Pohopoco Creek, a tributary of the Lehigh River) to meet the Trenton flow target are used to help repel, or flush back, the salt-laced water in order to protect the drinking water intakes in the downstream urban areas of Philadelphia and Camden. Water supply storage in these two lower basin reservoirs, both owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is financed by surface water users under a water charging program implemented by the DRBC.

Storage in Blue Marsh and Beltzville reservoirs is used to trigger drought warning and drought operations in the Lower Delaware River Basin – that portion of the basin downstream of Montague, N.J. This allows for reductions in the Trenton flow target and the New Jersey diversion when lower basin conditions are drier than in the upper part of the basin. Accordingly, lower basin operations are controlled by both basinwide or lower basin storage triggers, with the most limiting restrictions controlling.

Merrill Creek Reservoir, a pumped storage facility located near Phillipsburg in Warren County, N.J., releases water to replace evaporative water losses (“consumptive use”) caused by power generation when the basin is under DRBC-declared drought operations. Releases are made during both basinwide and lower basin drought warnings and droughts whenever the flow at Trenton drops below 3,000 cfs for at least five consecutive days.

Merrill Creek is owned by energy corporations and is designed to augment flow in order to allow power plants in the basin to continue to operate during drought conditions. According to DRBC:

u. Each electric generating unit which is a Designated Unit from EXHIBIT III of ATTACHMENT 2 shall be exempt from curtailment by the DRBC so long as the freshwater equivalent consumptive use resulting from the operation of that unit is being replaced by Compensation Releases from the MCR or from other sources approved by the Commission.

PSEG has significant interests in Merrill Creek, including assuring sufficient river flows to operate existing power plants and to provide sufficient polling water for their proposed new nuclear plant.

DRBC may find this PSEG testimony to NRC of interest, particularly regarding drought induced migration of the salt line:

As discussed below, the Merrill Creek Reservoir is not required for any safety cooling purposes for a new plant at the PSEG Site. PSEG considers it likely that it could transfer water rights from another PSEG-owned facility or it could obtain the water rights from a third party, if necessary, for a new plant at the PSEG Site. If PSEG proceeds with a combined license (COL) that references the ESP, then PSEG would need to consider any new and significant information related to water use and availability, which would include water allocation from the Merrill Creek Reservoir. The NRC Staff would consider PSEG’s new and significant evaluation and could consider other information related to water rights from the Merrill Creek Reservoir.

Q8. What is the purpose of the Merrill Creek Reservoir?

A8. The Merrill Creek Reservoir is used for low flow augmentation of the Delaware River during times of drought. The Merrill Creek Reservoir allows certain power plants, classified by the DRBC as “designated units,” to continue to withdraw water from the Delaware River for power generation during declared drought warnings or emergencies. The DRBC approved a Docket, authorizing construction in 1984 with the reservoir being placed in service in 1988. The current Docket for the Merrill Creek Reservoir is provided as Exhibit PSEG014.

Q12. What would happen if there was negligible flow in the Delaware River?

A12. As stated in Safety Evaluation Report (SER) Section 2.4.11.4.2 (Exhibit NRC003), even with negligible flow at Trenton, NJ (1.0 cubic feet per second (cfs)), tidal flow rather than freshwater flow is capable of providing ample and sufficient cooling water supply for the PSEG Site.

Isn’t it comforting to know that PSEG engineers have concluded that their nuke plants would continue to operate, while the Delaware River virtually ran dry (1 CFS) and there was a regional water supply crisis?

As DEP scientists warned, perhaps there is “trouble ahead” if drought conditions persist.