DEP Discovers Discrimination – Dumps Environmental Justice Issue in Christie’s Lap

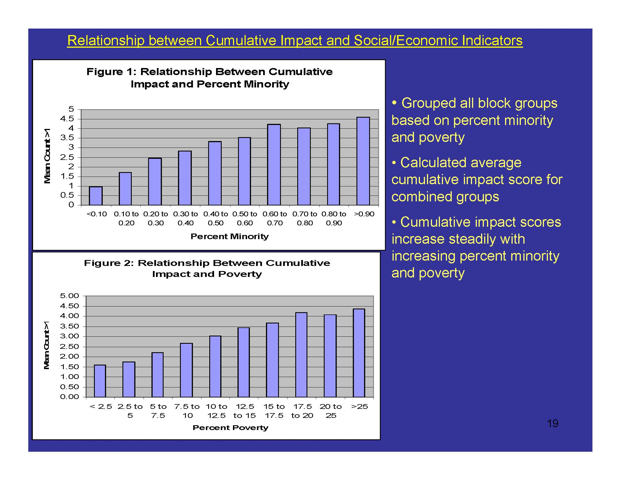

DEP data show a direct relationship between pollution impacts and race and income. Poor and minority communities are disproportionately impacted, compared to white wealthy communities. The poorer and higher the percentage of minority residents, the worse the environmental impacts. The DEP’s own data confirm longstanding claims made by environmental justice advocates. Source: NJDEP

DEP’s own data confirm longstanding claims made by environmental justice advocates

Colandus Francis, NAACP Camden County traced the history and spoke of the significance of the St. Lawrence cement US District Court decision

[Update below]

On Wednesday December 2, 2009, something remarkable and historic happened in Trenton, NJ at the meeting of the NJ Environmental Justice Advisory Council.

Although it surprised not a single environmental justice advocate in the room (no one even mumbled a Claude Raines “I’m shocked, just shocked, to find racism here”), it was a major concession and damning admission by the DEP bureaucracy. Look at the above chart, and then follow me.

More than 20 years ago, the groundbreaking United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice 1987 Report “Toxic Waste and Race“ launched the national environmental justice movement. That Report documented that black communities were disproportionately targeted for waste facilities.

Dr. Lewis, EJAC member, spoke of educating a new generation of black environmental activists

Almost 10 years ago, US District Court judge Stephen Orlofsky validated environmental justice concerns in Camden NJ and issued an injunction to block construction of the St. Lawrence cement plant. Orlofsky found that the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) had violated the civil rights of the African-American and Hispanic residents, who comprise 90 percent of the residents in the census tract where the St. Lawrence cement facility is located, after DEP issued an air pollution permit to the plant.

Orlofsky found the state DEP failed to consider the cumulative impacts posed by pollution from industrial sources already located in the primarily minority community. Orlofsky wrote:

“Much of what this case is about is what the NJDEP failed to consider … It did not consider the pre-existing poor health of the residents of Waterfront South, nor did it consider the cumulative environmental burden already borne by this impoverished community. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the NJDEP failed to consider the racial and ethnic composition of the population of Waterfront South.” (emphasis mine) South Camden Citizens in Action v. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 145 F. Supp. 2d 505 (D.N.J. 2001). )

Sharon Brown, EJ Advisory Council member, did not mince words and spoke of “endemic problems at DEP” and the need to enforce existing DEP regulations in EJ communities, and hold DEP and polluters accountable.

Now, after years of denial, followed by obfuscation, and finally progressing to supporting rhetoric (including a recent Corzine Executive Order #131), the NJ State Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has discovered discrimination* (*I knowingly am using that term colloquially – the data only support disproportionate impact, which does not legally prove the intent required for discrimination for civil rights law enforcement).

I am posting this data now, before DEP can run away from it or ignore it. Suggest you download it now. See: DEP Powerpoint Presentation For a brief discussion of this data and the methodology, see: DEP Technical Paper . For access to DEP’s Environmental Justice program, see this link

Briefly, DEP considered 9 indicators of environmental and/or public health impact: 1. cancer rates; 2. diesel emissions; 3. ambient benzene levels (a carcinogen); 4. traffic (all); 5. traffic (trucks); 6. density of DEP regulated industrial facilities; 7. density of toxic waste sites; 8. density of dry cleaners (toxic air emissions) and 9. density of junkyards.

For every single one of those indicators, the adverse impacts increased directly as the percentage of minority and poor residents increased.

DEP data conclusively demonstrates that poor and minority communities bear disproportionate impacts.

The strength of the correlation between race and income and adverse environmental & health impact demands that DEP take action to remedy this injustice. DEP must enforce existing environmental regulations to mitigate these impacts and develop tough new standards to prevent and better protect already over-burdened EJ communities.

Jeanne Herb, political appointee and Director of DEP Science and Policy

But Jeanne Herb, Director of DEP’s Office of Science and Policy, repeatedly refused to even discuss what DEP would do with these findings that they can no longer deny.

Herb warned the Advisory Council that any discussion of implementation issues were beyond the scope of the meeting and off the table. Herb said that DEP was unwilling to make any commitment to do anything to implement these findings because they were “management” issues and DEP “was in transition”. So, she basically dumped this issue in the lap of the new Christie Administration.

NJBIA (l) and Chamber of Commerce (r) lobbyists dodged a bullet

At the start of the meeting, the NJ Business and Industry Association and Chamber of Commerce lobbyists looked like scared white guys.

My guess is that they feared that the outgoing Corzine administration would live up to the spirit of his own Executive Order 131 and be loyal to a democratic base urban constituency and propose stringent new environmental justice regulations and/or announce an urban enforcement initiative. But after they heard Herb concede, I could sense their apprehension leave like the air coming out of a balloon. Shortly thereafter, they departed the meeting and arrogantly didn’t remain for the DEP staff’s technical presentation of the smoking gun data.

What will Christie do? We will keep you posted.

All eyes are now on Dave Pringle of the NJ Environmental Federation, the token environmentalist on the Christie Environmental Transition Team.

But, pictures don’t lie – Dave clearly seemed a lot closer to the NJBIA and Chamber lobbyists than the environmental justice and urban advocates.

Dave Pringle (l) NJEF sits with and confers with fellow lobbyists from the Chamber of Commerce and Business & Industry Association

[Update: I thought it worthwhile to excerpt some of Judge Orlofsky’s decision to show how lame the DEP has been and remains with respect to a total failure to implement any of their rhetoric (and why is it that a federal judge use harsher language to call out DEP than so called NJ EJ activists?): see: South Camden Citizens v. Nj Dept. of Environ., 145 F. Supp. 2d 446 (D.N.J. 2001)

Finally, the NJDEP’s insistence that its obligation to Plaintiffs under Title VI does not go beyond ensuring compliance with the NAAQS is completely undermined by the NJDEP’s own recognition, in numerous fora, that it has precisely such an obligation under Title VI. On October 22, 1998, NJDEP Commissioner Shinn issued the first of several Administrative Orders acknowledging the NJDEP’s obligation under Title VI. See Administrative Order No. 1998-15 at www.state.nj.us/dep/equity/ao98-15.htm (visited March 27, 2001). In this Administrative Order, Commissioner Shinn established the NJDEP’s Advisory Council on Environmental Equity (Advisory Council). Id. The NJDEP defined environmental equity as “the fair and equitable treatment in environmental decision-making of the citizens of all New Jersey communities regardless of race, color, income, or national origin. Fair and equitable treatment means that no population should bear disproportionate amounts of adverse health and environmental effects.” Environmental Equity Defined, at http:www.state.nj.us/dep/equity/define.htm (visited March 27, 2001). The purpose of the Advisory Council is to “provide advice and guidance to the Commissioner and to assist the Department as it implements an environmental equity policy and a process” The Advisory Council was created “in recognition of state and federal concerns that minority and low-income populations may be experiencing a greater impact from pollution than other communities.” Id.

158. Furthermore in early 2000, Commissioner Shinn issued Administrative Order 2000-01, which took effect immediately. Administrative Order 2000-01, at www.state.nj.us/dep/equity/ao00-01.htm (visited March 27, 2001). In this Administrative Order, Commissioner Shinn discussed responsibilities of the Advisory Council and identified environmental equity implementation strategies to be implemented by the NJDEP. Pursuant to these strategies, the NJDEP committed to: (1) work with the Advisory Council and permit applicants to identify mechanisms for community notification regarding application for new, modified, or renewal permits, as early as possible in the permit review process; (2) develop guidance for permit applicants for the administration of an effective environmental equity community outreach process; (3) establish a mechanism for community outreach at the earliest possible stage of the permit application process; (4) utilize technical screening tools such as the GIS and TRI to identify potential environmental equity issues at the earliest feasible stage of the permitting process; (5) participate in discussions among permit applicants and local community stakeholders and attempt, when possible, to include in permits conditions that the permit applicants and community stakeholders have agreed upon; (6) facilitate ADR between permit applicants and stakeholders in the case of disputes; (7) work with permit applicants to facilitate accessibility, understanding, and transfer of technical and scientific data to local communities; and (8) provide ongoing environmental equity training to appropriate NJDEP managers and staff. Id. According to the NJDEP’s website, this policy has been approved by the Advisory Council and is currently being “refined†in order to “ensure that the final product can be effectively incorporated into the permitting process.” The Policy and Process, www.state.nj/us/dep/equity/policy.htm (visited March 27, 2001).

159. It is the Court’s understanding that none of the policies or procedures referred to in the Administrative Orders have been implemented. Counsel for the NJDEP did not cite or otherwise describe or refer to any of the policies, the grant, or the administrative orders the Court has just described above. Indeed, when asked if she had any understanding of New Jersey’s Environmental Equity Program, Dr. Atay, Chief of the NJDEP’s Bureau of Air Quality Control and Hearing Officer for the SLC permit, stated that she had “none.” Atay Dep. at 62. Dr. Atay confirmed that “no matter what is in [an applicant’s permit] application, [she] and [the Bureau’s permitting staff] would look only for information that’s relevant to the question of would there or would there not be a violation of environmental law” Id. at 72-73.

160. Nevertheless, it is entirely clear from the Court’s review of Commissioner Shinn’s Administrative Orders that the NJDEP is aware that its obligations under Title VI extend beyond ensuring that permitted facilities do not violate environmental laws, and in fact include considering claims, such as Plaintiffs’ in the present case, that a particular permit will result in an adverse, disparate impact in violation of Title VI.

161. From this Court’s review of Title VI, the EPA’s implementing regulations to Title VI, the EPA’s administrative Guidances, the Select Steel decision, and NJDEP Commissioner Shinn’s own administrative orders, this Court concludes that the NJDEP’s interpretation of Title VI in the present case is not only erroneous, but would eviscerate the intent of Title VI, namely, to prevent agencies which receive federal funding from having the purpose or effect of discriminating in the implementation of their program on the basis of race, color, or national origin. 42 U.S.C. §2000d-1. The NJDEP has not cited a single source of statutory, regulatory, or case law which supports its position, and this Court found none. Accordingly, I shall grant Plaintiffs’ request for a declaratory judgment that the NJDEP and Commissioner Shinn have violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by failing to consider the potential adverse, disparate impact of the SLC facility’s operation on individuals based on their race, color, or national origin, as part of its decision to permit SLC’s proposed facility.